chesapeake bay

“I got eelgrass veins and brackish blood, I wrote my name in the tidal mud.” Daniel Kimbro from the song “Cape Charles.”

“I got eelgrass veins and brackish blood, I wrote my name in the tidal mud.” Daniel Kimbro from the song “Cape Charles.”

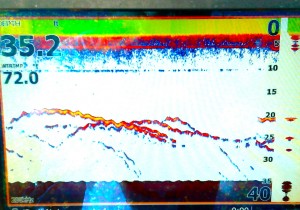

Eelgrass – it’s not something we’re used to seeing much in the Maryland portion of the Chesapeake Bay. According to the Maryland DNR website, it’s most likely found in high salinity areas of the Chesapeake Bay, approximately from the Choptank River south to the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Charles and in the smaller  coastal bays. Because of poor water quality, bay grasses are at historically low levels, so it’s a little odd that we’re seeing eelgrass farther north than usual this summer. It’s probably a result of high salinity coupled with sustained warmer temperatures – we’ve just come through the warmest twelve consecutive months ever recorded in the United States. On my StructureScan sonar, eelgrass and its cousin wild celery grass, looks like underwater fields of waving amber grain. Baitfish hide in it, and rockfish love it.

coastal bays. Because of poor water quality, bay grasses are at historically low levels, so it’s a little odd that we’re seeing eelgrass farther north than usual this summer. It’s probably a result of high salinity coupled with sustained warmer temperatures – we’ve just come through the warmest twelve consecutive months ever recorded in the United States. On my StructureScan sonar, eelgrass and its cousin wild celery grass, looks like underwater fields of waving amber grain. Baitfish hide in it, and rockfish love it.

Suspended fish, I hate ‘em. Scattered fish suspending in deep water is one of the most difficult situations a light tackle angler will encounter on the Chesapeake Bay. In years past, I’ve refused to target suspended fish. I’d rather run fifteen additional miles looking for stripers feeding off the bottom than fool with the picky little snots. But, as Bob Dylan might say, The Times, They Are a Changin’. Bad water makes everything different. As predicted in my last entry, low oxygen levels have led to prolific algae blooms in the tributary rivers and in some areas of the main stem of the Bay. Conditions are worse around the western shore rivers since more people live there and there is more pollution.

Suspended fish, I hate ‘em. Scattered fish suspending in deep water is one of the most difficult situations a light tackle angler will encounter on the Chesapeake Bay. In years past, I’ve refused to target suspended fish. I’d rather run fifteen additional miles looking for stripers feeding off the bottom than fool with the picky little snots. But, as Bob Dylan might say, The Times, They Are a Changin’. Bad water makes everything different. As predicted in my last entry, low oxygen levels have led to prolific algae blooms in the tributary rivers and in some areas of the main stem of the Bay. Conditions are worse around the western shore rivers since more people live there and there is more pollution.

Pollution, especially nutrients like nitrates and phosphorus get into the Bay as a result of raw sewage dumping, storm-water runoff, and excessive fertilizer use. This makes the water very fertile, so small microscopic plants such as algae grow rapidly. The algae cells block sunlight, then die and sink to the bottom creating areas of low oxygen where fish can’t survive. Since dissolved oxygen levels were already at record lows this year, it didn’t take long for the blooming and decaying cycle to use up whatever oxygen was left. Read More!

We’ve enjoyed a pretty good spring of light-tackle fishing on the Chesapeake Bay. Water temperatures warmed early, then leveled off through the end of April into May. Top-water casting is good right now at some places. Some anglers are even sight-casting surface lures and flies to cruising fish on shallow oyster bars near the mouths of the rivers. The water in some parts of the Upper Bay is clearer than I’ve ever seen it. While that makes surface fishing enjoyable, it also makes jigging tough since it’s easier for stripers to distinguish the difference between our lures and baitfish. The clear water looks nice, but there’s a big problem lurking below the surface: Low dissolved oxygen (DO). Measured in milligrams per litre, dissolved oxygen levels were recorded at 1.04 on the bottom beneath the Bay Bridge in April. That’s lower than they’ve been in twenty-five years. Look out for big algae blooms coming soon. Salinity also peaked to record levels in April. Last spring, Bay Bridge salinity was 4.20 ppt. This year, it’s more than twice that at 10.50 ppt. DO levels are also low in Eastern Bay, although salinity there is closer to normal. What does this mean for the fishing? Read More!

We’ve enjoyed a pretty good spring of light-tackle fishing on the Chesapeake Bay. Water temperatures warmed early, then leveled off through the end of April into May. Top-water casting is good right now at some places. Some anglers are even sight-casting surface lures and flies to cruising fish on shallow oyster bars near the mouths of the rivers. The water in some parts of the Upper Bay is clearer than I’ve ever seen it. While that makes surface fishing enjoyable, it also makes jigging tough since it’s easier for stripers to distinguish the difference between our lures and baitfish. The clear water looks nice, but there’s a big problem lurking below the surface: Low dissolved oxygen (DO). Measured in milligrams per litre, dissolved oxygen levels were recorded at 1.04 on the bottom beneath the Bay Bridge in April. That’s lower than they’ve been in twenty-five years. Look out for big algae blooms coming soon. Salinity also peaked to record levels in April. Last spring, Bay Bridge salinity was 4.20 ppt. This year, it’s more than twice that at 10.50 ppt. DO levels are also low in Eastern Bay, although salinity there is closer to normal. What does this mean for the fishing? Read More!

![0321120733a[1]](http://www.chesapeakelighttackle.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/0321120733a1-300x225.jpg) “I only write when I’m inspired,” wrote William Faulkner. I’d find that statement comforting if he hadn’t followed it with, “and I’m inspired every morning at 9:00 AM.” Lately, my every-morning-at-9:00 AM-ritual hasn’t included much writing. Oh, I’ve had plenty to write about, it’s just that I’ve over-committed myself (again) so that every spare waking minute seems filled with obligation. When I have a spare hour, I usually go fishing. Since I bet you’d much rather hear about the fishing than the excuses, I’ll dive right in.

“I only write when I’m inspired,” wrote William Faulkner. I’d find that statement comforting if he hadn’t followed it with, “and I’m inspired every morning at 9:00 AM.” Lately, my every-morning-at-9:00 AM-ritual hasn’t included much writing. Oh, I’ve had plenty to write about, it’s just that I’ve over-committed myself (again) so that every spare waking minute seems filled with obligation. When I have a spare hour, I usually go fishing. Since I bet you’d much rather hear about the fishing than the excuses, I’ll dive right in.

There’s nothing more inspiring than a big fish. That’s Uncle Phill Anderson in the cover shot holding up a nice light-tackle fish he jigged up on a recent foggy morning in the mid-Bay. (Shhh, don’t tell the meat-fleet we’re picking off fish of this class with light tackle. It might catch on!) When I left off a month ago, I was smack in the middle of a series about strike triggers. I’m discussing why striped bass attack a lure, and how they are attracted to their prey. As previously mentioned, almost any lure or technique will work on hunger-feeding fish. Unfortunately, most of us don’t have the time or resources to always go fishing at the places where hungry fish are most abundant. We have to fish in the limited time we have available, and usually very close to home. While we may occasionally encounter groups of ravenous fish, most of the stripers in our neighborhoods are pretty hard to catch. In order to be consistently successful, we have to provoke strikes from fish that may not be inclined to bite by appealing to their five senses. I’ve written about sight, sound, and feel. This entry completes the strike triggers series with a look at smell and taste. Read More!

In the last CLT entry, I wrote about the five reasons why Chesapeake Bay stripers attack a lure: hunger, reaction, competition, territory protection, and curiosity. When fish are hungry, they’re easy to catch. Almost any lure or technique will work on hunger-feeding fish. Unfortunately, most of us don’t have the time or resources to constantly run around looking for schools of voracious fish. If you’re like me, you have to fish in the limited time you have available, and you probably stay close to home. While we may occasionally happen upon groups of ravenous fish, most of the stripers we encounter are hard to catch. In order to be consistently successful, we have to provoke strikes from fish that may not be particularly inclined to bite. Strike producing lures are especially important right now since we have trophy rockfish migrating in and out of the Bay. Our chances for catching-and-releasing a 50-pounder on light tackle are better than at any other time of year, but migrating fish have other things on their minds besides eating. Big fish get bigger by being smart and getting smarter. To catch them, we need to cast lures that will provoke strikes by appealing to their five senses; sight, sound, smell, feel and taste. I call the formula 5 by 5. By that, I mean we can consider the five reasons why fish strike, then use lures designed to appeal to each of their five senses in order to come up with the best of all possible strike triggers. In this installment we’ll look at striped bass eyesight. Read More!

In the last CLT entry, I wrote about the five reasons why Chesapeake Bay stripers attack a lure: hunger, reaction, competition, territory protection, and curiosity. When fish are hungry, they’re easy to catch. Almost any lure or technique will work on hunger-feeding fish. Unfortunately, most of us don’t have the time or resources to constantly run around looking for schools of voracious fish. If you’re like me, you have to fish in the limited time you have available, and you probably stay close to home. While we may occasionally happen upon groups of ravenous fish, most of the stripers we encounter are hard to catch. In order to be consistently successful, we have to provoke strikes from fish that may not be particularly inclined to bite. Strike producing lures are especially important right now since we have trophy rockfish migrating in and out of the Bay. Our chances for catching-and-releasing a 50-pounder on light tackle are better than at any other time of year, but migrating fish have other things on their minds besides eating. Big fish get bigger by being smart and getting smarter. To catch them, we need to cast lures that will provoke strikes by appealing to their five senses; sight, sound, smell, feel and taste. I call the formula 5 by 5. By that, I mean we can consider the five reasons why fish strike, then use lures designed to appeal to each of their five senses in order to come up with the best of all possible strike triggers. In this installment we’ll look at striped bass eyesight. Read More!

This is just a short response to an article in the Sunday edition of the Annapolis Capital. I’ll preface by saying that I consider the writer, Captain Chris Dollar, a friend. I also know him to be an excellent fisherman. I was just speaking to a fishing buddy yesterday about how excited I am that he has opened a new kayak and biking store near Kent Narrows. A genuine nice guy, I wish him the best in everything he does and I encourage everyone to stop by his new store. The following is my letter to the editor of the Annapolis Capital in response to his disagreement with my recent ChesapeakeLightTackle.com entry about wild-caught Chesapeake oysters. That entry has now received over 15,000 individual page views:

This is just a short response to an article in the Sunday edition of the Annapolis Capital. I’ll preface by saying that I consider the writer, Captain Chris Dollar, a friend. I also know him to be an excellent fisherman. I was just speaking to a fishing buddy yesterday about how excited I am that he has opened a new kayak and biking store near Kent Narrows. A genuine nice guy, I wish him the best in everything he does and I encourage everyone to stop by his new store. The following is my letter to the editor of the Annapolis Capital in response to his disagreement with my recent ChesapeakeLightTackle.com entry about wild-caught Chesapeake oysters. That entry has now received over 15,000 individual page views:

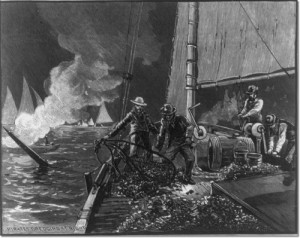

In his Outdoors column of March 4, 2012 Captain Chris Dollar writes in the Annapolis Capital:

(As a sidebar, I read a recent blog post in which the writer claimed people shouldn’t eat wild Chesapeake oysters because it’s bad for the bay. In all my conversations with experts over the years I’ve never heard that as a cause of what ails bay oysters.) Moreover, banning the catch of wild fish or oysters seems at odds with the state’s efforts to promote Maryland seafood. Catch local, eat local, right?

Dear Editor — Since Captain Dollar is speaking of my comments in my blog, Chesapeakelighttackle.com entry Jan 25, “Oysterholism,” I think it is only fair to point out that I am a big advocate for farm-raised Chesapeake oysters. I consider them to be among the best in the world, and encourage everyone to eat them. However, I believe Captain Dollar may be conversing with the wrong experts because,according to research published by the University of Maryland in 2011 in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series (Vol. 436), “the oyster population in the upper Chesapeake Bay has been estimated to be 0.3% of population levels of early 1800s due to overfishing, disease, and habitat loss.” If discouraging the eating of the last 0.3% of wild-caught oysters is at odds with the state’s efforts to promote Maryland seafood, I suggest the state take another look at it’s policies. I don’t know about my good friend Captain Dollar, but I don’t want to be the one who eats the last wild-caught oyster from the Chesapeake Bay.

Respectfully, Shawn Kimbro Read More!